I’m guessing you got quite a few e-mails today. But have you ever had a v-mail? That sounds like some new term for video e-mail, but it actually dates back to World War II. If you are in Europe, the term was Airgraph — not much more descriptive.

If you make a study of war, you’ll find one thing. Over the long term, the winning side is almost always the side that can keep their troops supplied. Many historians think World War II was not won by weapons but won by manufacturing capability. That might not be totally true, but supplies are critical to a combat force. Other factors like tactics, doctrine, training, and sheer will come into play as well.

On the other hand, morale on the front line and the home front is important, too. Few things boost morale as much as a positive letter from home. But there’s a problem.

On the other hand, morale on the front line and the home front is important, too. Few things boost morale as much as a positive letter from home. But there’s a problem.

While today’s warfighter might have access to a variety of options to communicate with those back home, in World War II, communications typically meant written letters. The problem is ships going from the United States to Europe needed to be full of materials and soldiers, not mailbags. With almost two million U.S. soldiers in the European Theater of Operations, handling mail from home was a major concern.

British Mail Hack

The British already figured out the mail problem in the 1930s. Eastman Kodak and Imperial Airways (which would later become British Airways) developed the Airgraph system to save weight on mail-carrying aircraft. Airgraph allowed people to write soldiers on a special form. The form was microfilmed and sent to the field. On the receiving end, the microfilm was printed and delivered as regular mail.

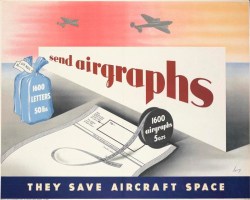

A poster at the time (see left) claimed that 1,600 Airgraph letters required 5 oz compared to 50 lbs of real paper mail. By 1941, the first 70,000 Airgraphs were sent to overseas troops. Eventually, soldiers could use the same service to return mail home.

A poster at the time (see left) claimed that 1,600 Airgraph letters required 5 oz compared to 50 lbs of real paper mail. By 1941, the first 70,000 Airgraphs were sent to overseas troops. Eventually, soldiers could use the same service to return mail home.

The Airgraphs were cheap (3 pence), but were only 2×3 inches, so they were more or less small postcards. All of this took equipment at both ends but by 1944, Airgraphs were available throughout the European theater and other parts of the Commonwealth.

V-Mail

The US version of Airgraph was V-Mail. A 7×9 inch form went through censors and then went to microfilm. The destination printer would print the output at 60% or just over 4×5 inches.The National Postal Museum claims that 150,000 one-page letters would take 37 mailbags weighing over 2,500 pounds. The same amount of V-Mail fit in a single 45-pound sack.

There was another advantage to Airgraph and V-Mail. Security. Invisible ink, microdots, and microprinting all fail to get past the process of putting the messages on film.

Lessons Learned

With today’s myriad communications methods, V-Mail isn’t making a comeback. But it is a great example of how outside-the-box thinking can accomplish. Reducing mail weight to 1.8% and volume to 2.7% would have sounded like impossible goals, but Kodak did it.

The other thing that interests me is how quickly high-tech (because, in the day this was high-tech) can rise to solve a problem and then become almost completely forgotten. How many kids born this week will know what an LED watch is or a dial up modem? How about a daisy wheel printer or a floppy disk? You have to wonder what other tech is out there almost completely forgotten and that’s where Retrotechtacular comes in.

More recent in my lifetime, Air Mail envelops from the post office came unfolded and were very thin paper, you wrote on the inside of the envelope then folded it up and licked the glue like a regular envelope, other paper for air mail was real thin and called onion skin

Heh, didn’t fully dawn on me that aerograms had been phased out until I went a googling just now. Think I’ve seen generic ones available still though, that will need stamps at going rate, whereas the postal authority issued ones were pre-paid.

We still have a pile of V-mail. “Victory mail” was what it stood for. My father sent it to my mother and her parents during the war.

Getting stuff past the censor was a game that lots of people played. In our family it involved using in-family knowledge. In one message my father wrote something like this: “I ran into Sylvia’s brother recently, and he said he would be in Baltimore around July 10th.” Had he said, “I’ll meet you in Baltimore on July 10th,” that would have been cut out. His sister was Sylvia, and he was her only brother. We knew that, but the Germans, the Japanese, and the censor did not.

Quick clarification question.

“The National Postal Museum claims that 150,00 one-page letters would take 37 mailbags weighing over 2,500 pounds.”

Is that meant to be 150,000 or 15,000?

https://postalmuseum.si.edu/victorymail/introducing/how.html

Officials estimated V-Mail saved up to 98% on cargo weight and space.

150,000 ordinary one-sheet letters

Weight 2,575 pounds

37 mail sacks required

150,000 V-Mail letters (in original form)

Weight 1,500 pounds

22 mail sacks required

150,000 V-Mail letters (microfilmed)

Weight 45 pounds

1 mail sack required

or 150,oo0?

Found the source of this statistic: https://postalmuseum.si.edu/exhibits/past/the-art-of-cards-and-letters/mail-call/v-mail.html

It’s 150,000

If anyone has more interest in this subject, go to ebay and search under Stamps for Airgraph.

Just think if we’d kept all that micro-film? Historians would have a field day.

There doesn’t seem to be any archive of the microfilm that I can find. I’m wondering if the film stock was recycled (or perhaps destroyed).

Here’s the article that seems to be the source of Vmail information for this post.

https://hackaday.com/2017/10/06/retrotechtacular-hacking-wartime-mail/#more-275329

There has been an industry around engraving grammophone records on old X-rays .

Maybe some of these found that path also.

On the other hand. During the war everything would have been scarce, including the material for those films.

There were collection points for worn out panty hoses for making parachutes back then.

Maybe they did, but it’s the kind of personal records they tend to put a 100 year lock on, so check back in 2044 or so

“The National Postal Museum claims that 150,00 one-page letters would take 37 mailbags weighing over 2,500 pounds.”

I first heard about this years ago and always wondered at the actual savings. Yes, a few long rolls of film weighed much less than 150,000 sheets of paper, but all those letters had to be photographed in the States, then they had to be turned into 150,000 photographic prints in the UK.

I’ve got to think that the process of making 150,000 sheets of photographic paper and the chemicals to develop them consumed an enormous pile of resources, transportation and manpower, which, presumably were in short supply in England, you know, with all the fighting a war and being bombed and such.

Probably many more resources than the avgas to move 2500 pounds of mail.

Even if the material was manufactured in the States and sent over on a slow boat (no time pressure since they weren’t ‘letters’ yet) it still seems like it would have been monumentally easier to just ship every stateside Post Office a few reams of super-thin paper with instructions “Tell every family to use this”. If the paper was too thin to withstand the rigors of military mail in a war zone, the flimsy letters could be put in heavier envelopes in England, which was a step with photo-mail anyhow.

Of course, as the article pointed out, it did give censors a chance to examine every letter going into a war zone, and I suppose that was not an insignificant thing.

I dont’ think it was just the weight, I think it was also the space the mail bags would take. the letters themselves would take up 37 bags(or 22 bags, depending on which size letter as noted above) while the filmed letters would take up 1 bag, that would leave 36 (or 21) bags of ‘space’ available for war materiel that was needed to be shipped overseas. This allowed them to still ship letters without impacting the other needed materiel to greatly at the same time.

About 1980, Canada Post had something sort of similar. You could take your letter to post office, where it would be scanned and sent across the county electronically, where it would be printed, stuffed in an envelope, and delivered locally. Useless for local mailings, I assume it did get things there faster if it wasn’t local. Touted as “electronic”, in retrospect it must have just been a fax system, no need for computers.

I can’t remember the cost, but I sent one once, so it couldn’t have been too premium. It was advertised at the beginning, but I don’t remember seeing much later, and I never saw a notice that it was ending.

Again, a hybrid system that probably wasn’t earlier, but later would be replaced by other things. They weren’t playing catch up then, just offering something somewhat cutting edge, yet with time it didn’t matter, the post office was obsoleted for letter mail.

Michael

I remember reading about an early FAX type system, I think the AP used it to wire photos and such, only worked with back and white stuff, more or less the document or photo was put on a rotating drum, where it was scanned by a photocell, on the other end an LED or a light of some kind would turn on and off over a photosensitive drum, scanning at the same rate as the drum and sensor on the original. From what I remember the process was similar to what was used in copiers but can’t recall the name of the system.

AP Wirephoto, first used in 1935. Earlier stuff existed. See https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Wirephoto

The laser printer (invented in the early 70s at Xerox by Gary Starkweather) was originally conceived as a technology for high speed fax transmission before Gary realized it would work very well as a computer printer.

https://hackaday.com/2016/11/04/retrotechtacular-fax-as-a-service-in-1984/

I like that very confident voice of the era.

Does it have a specific name, please (for that kind of voice)?

I think they’re generally a version of this, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mid-Atlantic_accent

Interesting, thank you!

:o)

There also was that time during the cold war, where the USPS looked into using cruise missiles for moving mail around.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Rocket_mail

https://99percentinvisible.org/article/firing-off-letters-u-s-postal-services-cold-war-missile-mail-project/

Wars not won with weapons. That Might not be Totally true…

Ya think? Manufacturing will bury the opponent under mountains of kazoos and slide whistles?

Much of the German weaponry in WWII was technically superior to that of their opponents, however Allied production was such that even if the Axis destroyed 4 tanks for every 1 that they lost, the Allies still came out ahead. With regards to planes, the Axis was out produced over 5 to 1.

The “technically superior” problem, where it was true, was that it took longer to make, longer to fix and was often not as reliable under harsh conditions. Then for anything motorised, germans had continual problems with inferior quality fuel and even supplies of that, while the allies were able to use high octane and run high compression or higher boost tubo/super charging.

On the allied side though, the Sherman was a particularly sucky tank to standardise on, good thing they could make so many.

Another thing was allies dumbed down their designs, so they had furniture and piano factories making aircraft parts etc. The Germans as far as I know, stuck to purpose built factories. Then compare things like the beautifully engineered MP40 to the STEN gun which was basically plumbing, and it’s no wonder allies could whack them out many to one.

Yet another factor, was that early in the war, Allies would run factories in 3 shifts, with as many replacement female workers as they could mobilise. Germans stuck a long time with single shifts and male workers. I believe about halfway through they started mobilising foreign workers, who even when they weeded out the actual saboteurs weren’t exactly doing their best efforts on Germany’s behalf. I think it was very late before they even introduced 2 shift working.

I imagine “good enough” has a very long history.

Just some clarification about the Sherman, for the first half of the war, it was a great tank. It remained a pretty good medium tank, problem was that most of the time it faced heavy tanks. It’s performance in North Africa against 2nd line German and Italian tanks, unfortunately gave the higher command the idea that it was close to invincible, so at that point, development basically froze. In comparison then to the Panzer IV and Tigers, evolved in hard battling the legendary T-34 on the Eastern Front, when it landed in France in 1944, it was a sucky tank, it needed more armor and it needed more gun. Attempts by crews and maintenance depots to up armor it with spare tracks and chunks cut out of disabled tanks made it over heavy, which slowed it down and strained it’s normally reliable mechanics.

And the germans overcomplicated things like artillery pieces. Where there were dozens of high tolerance parts for mechanisms where the american equivalent had 7. The tanks were especially problematic with this.

I watched PBS’s Secrets of the Dead: Deadliest Battle and they made the point too that Russian tanks took that lack of precision to an even higher art form. Casting turrets, they would never grind off the flash or casting marks. Just paint over it and make the next turret. The Russian Front was all about attrition and numbers of tanks destroyed. Germany tried making up for the deficit by commandeering tanks from every country it invaded. Which made things worse. They had 1.Czech tanks 2.Polish tanks 3.French tanks all mixed in with their own tanks. And they could NOT get spare parts for any of it, especially the commandeered tanks. They ran their tank corps. off of destroyed/broken tanks they could cannibalize for parts. A losing proposition always.

From what I understand a sledgehammer was standard equipment for the driver to get the transmission into gear on the russian tanks.

I believe that the Germans “farmed out” manufacture of parts on the Volksjager (People’s Hunter Jet Aircraft) but that was at the end of the war, so yea, it took Jerry a while to learn how to make stuff fast.

I had an old wartime Reader’s Digest with an article about silver barons refusing to let silver “go to war”. It said the recoil mechanism of a howitzer used pounds, not ounces of it. Anyone here know if that was the truth- or a cover for the Manhandle Project’s use of tons of silver?